History

On the road to Retro Haven

On the road to retro heaven, Tim Ross pulls up at the motel door.

If the billboard-sized signage and Vegas-inspired arrows didn’t attract you to Victoria’s first motel, owner Cyril Lewis devised an unusual ad campaign to entice travellers: "Your car in your bedroom." Being a former used-car salesman partly explains the "autoerotic" pitch. But Lewis understood a wider post-war obsession: Australia was in the grip of a love affair with America’s drive-in culture. The car brought freedom and liberation to travel, and in its wake left drive-in theatres, fast food restaurants and the motor hotel, or "motel". The Oakleigh Motel opened in 1957, the year Jack Keroauc published On the Road. "It seems unbelievable but people would drive past just to look at the Oakleigh Motel, because it was so new and modern," says Tim Ross, comedian, mid-century modern obsessive and author of a new pictorial history, Motel: Images of Australia on Holidays. "America had come to town."

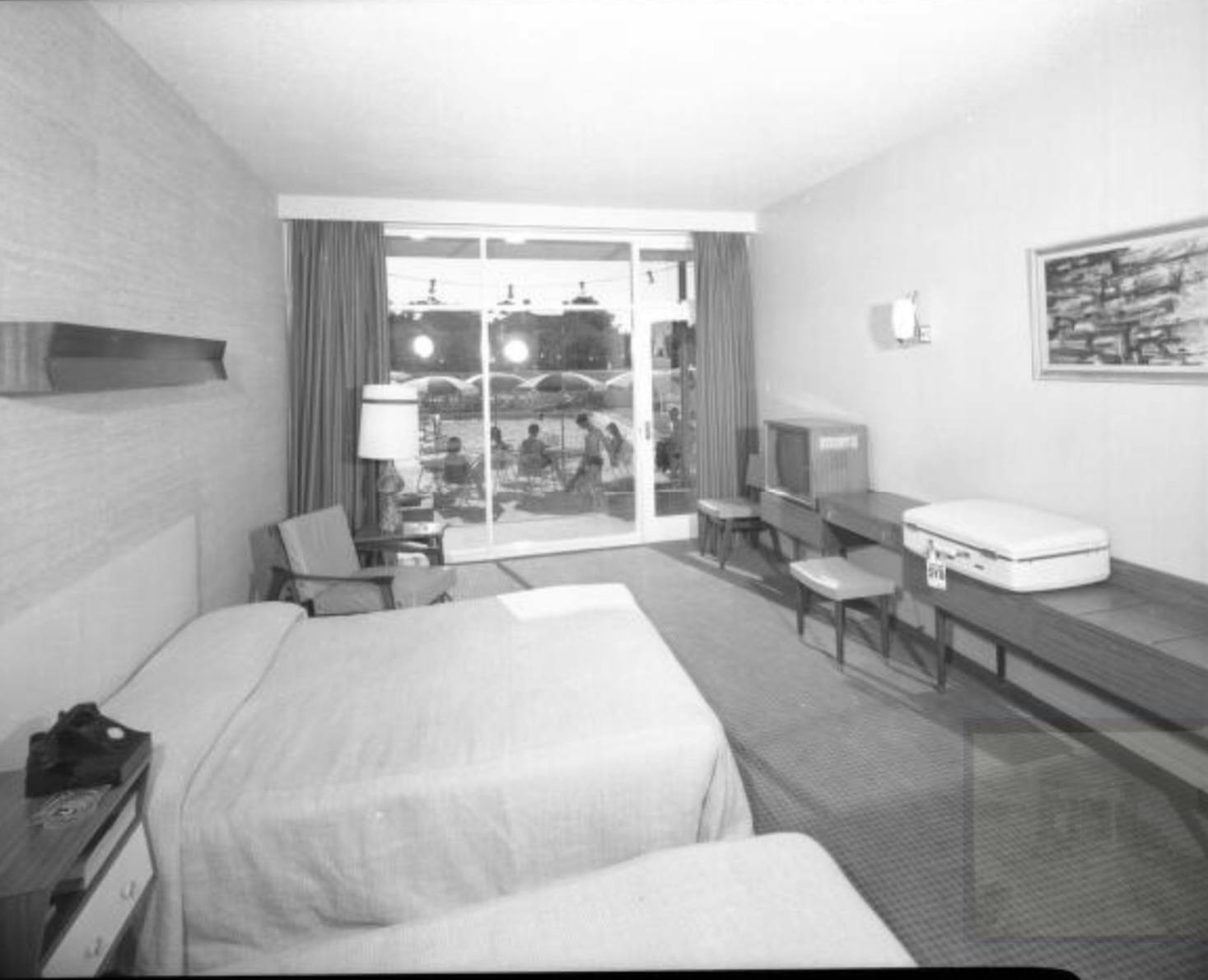

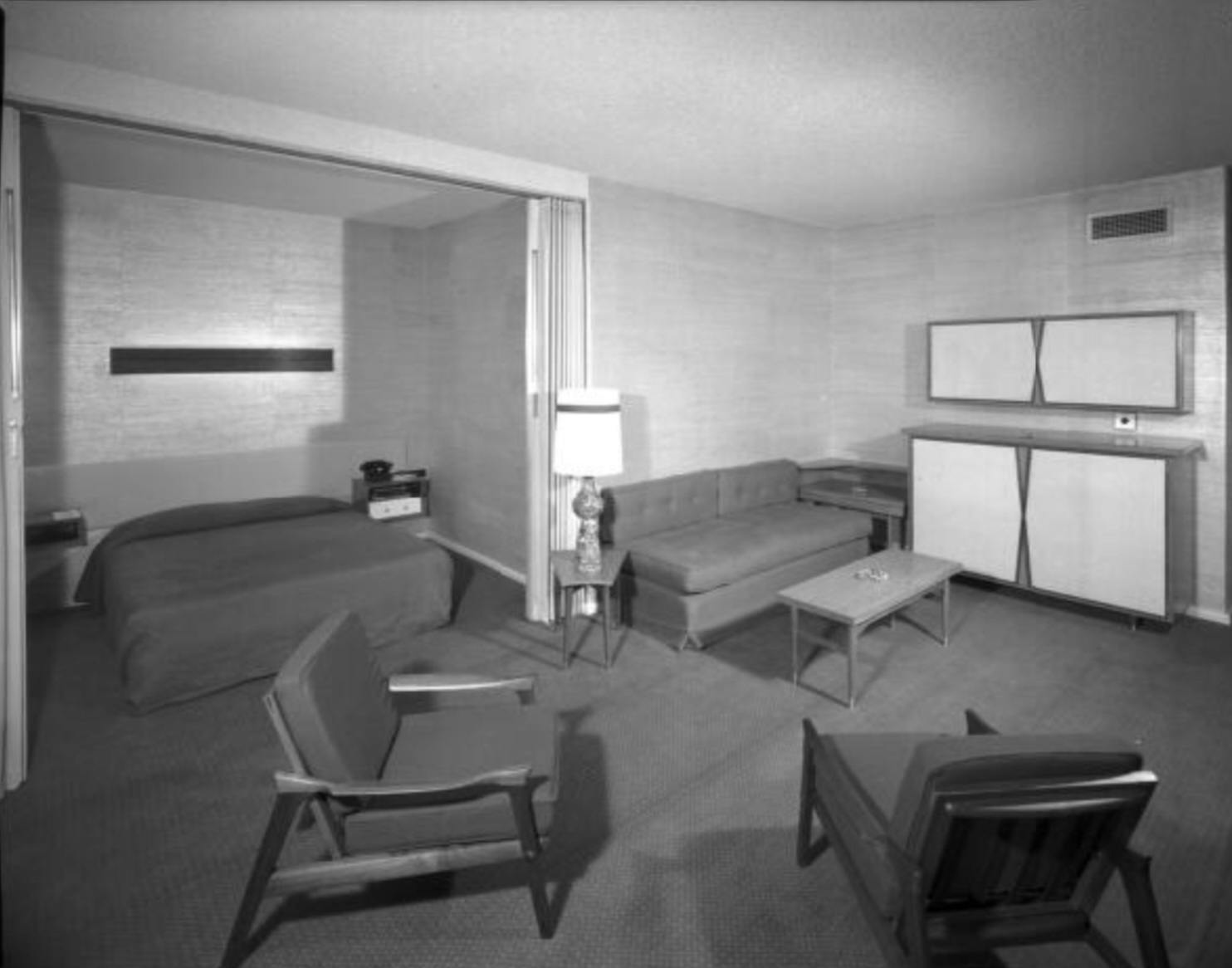

The Oakleigh’s outsized signage pointed to a butterfly roof, angled "zig-zag" rooms, sloping window walls and 43 self-contained rooms boasting individual bathrooms, and mod cons such as a telephone, air-conditioning, wall-to-wall carpet and venetian blinds. Equally thrilling, meals were delivered magically through a hatch.

Victoria was relatively late to the inexorable expansion of the popular motel, but the Gold Coast was in full grip. The El Dorado Motel was indicative of this Australian strain of vibrant Googie style: cartoonishly out of proportion, canted and often cantilevered, crowned and punctuated with futuristic Pop blasts of neon. Googie’s aesthetic apotheosis is the Las Vegas strip. Its signage – designed to be read at speed from a moving car – influenced a generation of postmodern architects. "What was incredibly interesting about the early motels in Australia was that they were all based on drawings or photos in magazines," Ross says.

Ross affectionately describes Australia’s motel pioneers as "cowboys" and "chancers". Alongside Lewis, people such as Bernie Elsey transformed the Gold Coast into the playground for Australia’s east coast, spicing up the beach culture with pyjama parties and meter maids. "It was frontier stuff," Ross says. In the impressive ABC TV series Streets of Your Town, and in his stand-up comedy Man about the House (which he stages in significant mid-century houses around the country), Ross has been a champion of good design. But he also holds affection for the not-so-good. Indeed, he seems to reside on memory lane, reminiscing about growing up in suburbia. For him, the motel is its logical extension and a literal nostalgia trip, a place to riff on what we all did on our holidays. The book was compiled with images sourced from Australia’s National Archives, and his new live show takes the journey further. "It’s based in history and leisure time and a chance for people to relive the holidays they had – to think about the precious nature of those memories that we had in motels with our families," he says. It’s not all glamour. Ross remembers trying "to fall asleep to the sounds of trucks rumbling by outside, their bulk rattling the wafer-thin windows and their headlights sneaking through the top of the nylon curtain to dance across the motel room ceiling". So why the wistfulness? "What’s interesting to me is the concepts of the experiences that unite us nationally," he says. "Every state has similar emotions when it comes to the idea of going to a motel. ‘Has it got a pool, dad?’ was said everywhere. It’s nice to hook into a simpler time and a very Australian thing to do. We used to mourn the bypassing of towns when a freeway went through. Now cheap flights bypass our own country." Ross revels in the range of childhood experiences, from the simple minutiae of kids excitedly jumping up and down on the bed to gargantuan roadside attractions such as the big banana and the big merino. Even the motel’s cramped quarters hold sentimental appeal. "At the time it didn’t bother me," he says. "We were all in one room. Mum and dad were happy-ish. We were away. We could all lie in bed and watch TV."

His book captions even recapture the cheesy postcards that document the Australian travel experience. "I wanted to be respectful to the National Archive and at times inject it with humour and sometimes paint small pictures," he says. "At the basis of it is that in a time of globalisation we have to keep telling our stories in different ways." Ironically it’s cultural colonisation that rankled Australia’s loudest critic of the motel, Robin Boyd. For him, the motel was a form of Austerica, an "austerity version of the American dream overtak[ing] the indigenous culture". "It flourishes best of all in Australia, which is already half overtaken by the hysteria," the acclaimed architect and cultural commentator wrote. "Austerica’s chief industry is the imitation of the froth on the top of the American soda-fountain drink. Its religion is ‘glamour’ and the devotees are psychologically displaced persons who picture heaven as the pool terrace of a Las Vegas hotel." While Ross is a Boyd admirer, he disagrees with the notion of Austerica. "Robin was deeply out of touch on what people liked," he says. "You’re fighting against what everyone sees on TV and wants." Evidently, America wasn’t all the Australian public wanted. Exotic theme motels sprang up: the Chinese-themed Cherry Blossom sprouted in Darwin, the boat motel "Boatel" moored in Mulwala, NSW, and the Polynesian-inspired Orchard Beach blossomed on Fraser Island. A Ross favourite is the colonial theme. Its marketing recipe was as simple as adding pineapple to transform a dish into Hawaiian – just add a white, painted wagon wheel. In 1958, Boyd had his own chance to design a motel. The Black Dolphin Motel in Merimbula offered suitably restrained signage, peeled log columns and exposed bricks. Boyd described it as an "architectural tranquillizer". It still survives today, though it has been much altered over the years. Arguably Boyd’s great innovation was placing the bathroom at the front of the unit, muffling the sound and lights of parking cars.

"From a design point of view it’s interesting how little was learnt from Boyd," Ross says. "The bathroom is still at the back, so the headlights wake you up." The heyday of the motel may be long gone, but some well-positioned coastal establishments, such as Halcyon House at Cabarita Beach and Rick Stein’s Bannisters at Mollymook, have been retrofitted and rekindle ’60s glamour. "The hard thing about motels in terms of saving them is they’re not particularly adaptable," Ross says. "They’ll mostly survive because people like having affairs."